Dublin’s Brendan Gleeson is one of those actors who always manages to crawl inside a character’s skin, creating fully actualized, riveting performances.

Some of his outstanding films include: “Far and Away,” “Michael Collins,” “Braveheart,” “The General,” “Lake Placid,” “Mission Impossible II,” “The Taylor of Panama,” “Gangs of New York,” “Troy,” “Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire,” “In Bruges,” “Green Zone,” “Safe House,” “The Butcher Boy,” and the most charming “The Grand Seduction.”

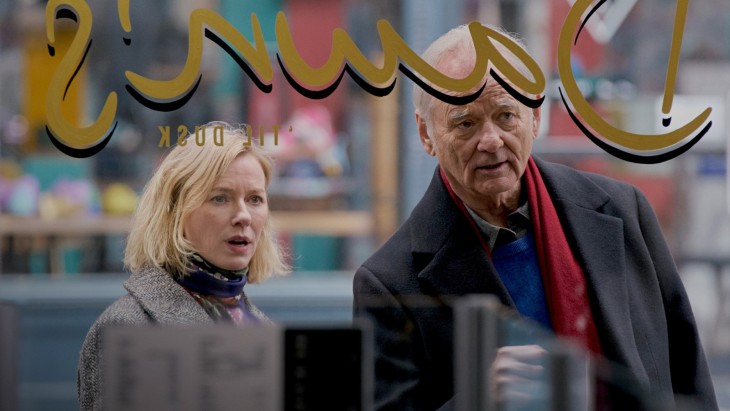

Gleeson’s latest film, currently playing in theatres, is “Calvary.”

Written and directed by John Michael McDonagh, Gleeson plays the lead role of Father James, a very kind priest in a small Irish parish who hears a shocking plan during a confessional.

This revelation sends him on an exploratory mission, which ultimately reveals his strength and humility especially through his relationship with his daughter, played by Kelly Reilly.

Without being a “spoiler,” the opening sequence is probably one of the most surprising and shocking scenes you’ll see in any film and hence kicks off the action in this thriller, a cliff-hanger until the very final shot.

Other members of this outstanding cast include Chris O’Dowd, Aiden Gillen, Dylan Moran, Isaach De Bankolé, Domhnall Gleeson, and M. Emmet Walsh.

Gleeson recently sat down with a select group of journalists and the following has been edited for content and continuity for print purposes.

Congratulations on yet another extraordinary performance.

Gleeson: Thank you very much.

You were quoted as saying “This script is for actors.” When you read the script, what was your first reaction?

Gleeson: I felt challenged and in an odd way, I felt reassured. What we talked about with John [director, John Michael McDonagh] was more or less on the page. I had an initial kind of a feeling that I knew this man as a human being through his daughter, which I wasn’t expecting and maybe we should see more of that. Obviously, I felt excited and all that because I understood culturally where he was coming from. I understood the issues and there was a lot of stuff that was second nature in the sense it was a very recognizable context for me.

Did you see Father James as an allegory for Christ?

Gleeson: No. I never felt Christ-like. I felt like a Samurai Warrior more than Christ in the sense he was a protector of whatever the essence of goodness is. There is a picture of the sacred heart that I remember thinking about where you see the actual heart. It’s open there for anybody to have a go at it. So, as Father James, whenever I put on the vestments for mass, in a way I felt that I had a suit of armor and in another way felt that I was stripping everything away. It was a very odd sensation. The notion of atoning for others’ pain and others’ sins in terms of the abuse that has been perpetrated by people of the cloth and absorbing people’s pain and trauma and taking it on yourself, that was Christ-like, but Christ knew who his father was. Father James is kind of working on his own faith and that this is actually a good idea.

Have you played a priest before?

Gleeson: I played Father Bubbles in “The Butcher Boy,” which was my favorite novel at that time, so to play that guy was interesting. He was a good priest too, but a little naïve, but this guy [Father James] is not naïve, which is more interesting to me.

Is there a certain responsibility in playing a priest?

Gleeson: In what way?

An inside view?

Gleeson: There was. I decided not to say what my own spiritual convictions are because I want people to watch the film without thinking there is any particular agenda going on with regards to faith or no faith or Catholic, or non-Catholic or anti-Catholic or whatever. I’m not being coy, but I just don’t think it’s a good idea for me to go into my own deal.

As you developed the character, were there any familiar childhood memories that came back?

Gleeson: Certainly. There were people in my childhood that kept me going back to that [his childhood]. There was a mentor of mine who was a Christian brother and was a hugely inspirational figure in my primary school. He was great mentor. My parents’ kind of faith was the one that I accessed more than anything more modern. I found there was clarity of purpose there, where before people had the kind of questioning that has been the norm for the last 30-40 years. It was kind of faith in humanity and a charity that I missed when it started to move on – just kindness or the ability to be able to go to a child who is lost.

Were there certain scenes that had a big impact on you?

Gleeson: The scene on the road was one of the scenes that resonated with me in a huge amount as a father. Today, you can’t talk to a girl on the road without being accused of something improper and if a child is lost in a supermarket, as a man you cannot take a child’s hand and bring her over to find her mother. Something is broken, you know?

Do you have children?

Gleeson: I have four lads, four sons who have been my greatest gift.

You’re stage-trained and your profile says that you did a lot of Shakespeare.

Gleeson: It’s a lie (laughter). I keep telling people that I’ve never done Shakespeare. I keep telling everybody that and think to myself, why not just take the credit for all those years in RADA (Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts), which I didn’t spend and get the degree without doing the work (laughter).

What was the genesis of events that led you to film?

Gleeson: When I left school, I hooked up with a bunch of guys who had been with my mentor as well and we got involved in theatre with the help of a particularly good English teacher who I could get on with. After a few years, I went back to college and was going to do a lot of different things. I hooked up with a group there. They were working in the Irish language and were putting on plays and rock concerts and all sorts of stuff in the Irish language. They developed a theatre company and this company grew bigger and bigger. We went out to find audiences that didn’t go to theatre and we wrote plays for them and brought them into a theatre they could identify with.

Were you also teaching at the same time?

Gleeson: I was teaching for 10 years and enjoyed it, but I was 34 at that point. I was writing plays and trying to direct plays. I was trying to act in plays. I was trying to put on a concert at school. I was trying to keep all the lads educated and decided that I couldn’t keep it up and had to do something.

Did you have professional aspirations?

Gleeson: I didn’t do all this with a view of becoming a professional actor. I did everything on my own terms. I didn’t feel that I had to go and advertise soap powder to keep my family fed and I enjoyed the teaching itself. But when I turned 34, I decided that 35 is not going to be a point of regret for me where I would say “I should have.” So, that opened up a second life for me.

With all the different kinds of characters you’ve played, do you build an inner life for your characters or does the character become alive just from the script itself. Also, how do you work with other actors?

Gleeson: It depends. I don’t have a particular process. Whatever I need to do is what I’m going to do. I don’t necessarily do “Method,” but I don’t mind if somebody else is doing it. It’s kind of great to join in and do improvisation and all that stuff around the work. I think essentially I can read a script and can understand and empathize with the characters to the extent where I can feel impact or the lack of it. Maybe it’s because of all the essays I read when I was teaching. It’s an important thing in my arsenal so I can distinguish pretty well what is a good script and what isn’t. You’ve already read the script and with a voice in your head and that’s the beginning of empathizing with the character and then you do whatever you need to do – whether it’s culture research or something else. I did Churchill, for example, which was a massive leap in terms of accent and culture. It was totally different from my life experience and I did a lot of research. That said, there are other times where the research gets in the way. So for me, you always approach every job with whatever you need to get it done.

Since you’ve worked with John before on “The Guard, do you have a shorthand in your communication?

Gleeson: He is such an exquisite writer with very sure cinematic vision that I feel very liberated in exploring what I find in the character. We share a general instinct in most areas, but we don’t always agree on things, which allows kind of a proper creative friction. I would tend to be a little bit more optimistic while he tends to be more nihilistic and then he writes these exquisitely tender scenes that are full of compassion and love.

What would people find out about you that would be unexpected?

Gleeson: In what way am I weird? (Laughter) Let’s turn this around. In what way are you weird? (Laughter) I don’t know but whatever it is, I’m going to keep it to myself because there’s so little left that is private, that anything I have, I’m going to hold onto for dear life (laughter).

I have one final question. You are a father, a husband and have a very successful career. What is the challenge in juggling everything?

Gleeson: I’m lucky to have an extraordinary partner. We decided to have the base at home in Dublin as the stability and there were sacrifices that she was required to make. It meant that my kids would not get hauled around. I got kind of lonely, but I had kids who were being looked after, so I was very lucky. It’s very difficult when two people have two careers to balance. So I have her to thank for my stable family life.

I wanted to tell you that I’ve been to Ireland three times on press trips sponsored by Tourism Ireland and absolutely loved it.

Gleeson: Have you been to Sligo?

Yes. As a matter of fact, I had dinner with this wonderful couple who are experts on Yeats. With the Lake Isle of Innisfree as the backdrop, the professor would read a poem in between delicious courses prepared by his physician wife. It was quite an unforgettable experience.

Gleeson: Lovely.

And, they love Americans.

Gleeson: Well, half of them are us! (Laughter)