No law annoys California developers more than the California Environmental Quality Act and they figure to win at least some changes to its strict 42-year-old rules next year.

They almost sneaked through a major softening of the state’s premier environmental law last September in the waning moments of the last legislative session, but were forced to back off in the face of heavy objections to softening the law without any public hearings at all.

CEQA requires sponsors of any building project or other development that will have a significant effect on the environment to write an environmental impact report assessing the effects of even its smallest aspects. Signed in 1970 by then-Gov. Ronald Reagan, the law was intended to supplement the National Environment Policy Act of 1969, signed by President Richard Nixon. That law demands an environmental impact statement for every significant action by any federal agency.

The national law, for just one example, is the reason why the U.S. Navy cannot practice gunnery on the western side of the military-owned San Clemente Island without first making sure it won’t affect migrating whales.

The state law has been used by environmentalists and others to obstruct countless projects, with legal challenges to the adequacy of EIRs often adding months and years to the planning cycle of projects as diverse as sports arenas and apartment buildings.

Business and development interests maintain they respect the way CEQA provides the public with information about the effects of projects large and small. Effects measured by EIRs include everything from public health considerations – would a new freeway create health risks from vehicle exhaust? – to increased traffic and potential danger to wildlife. Once identified, adverse impacts must be mitigated, often adding large sums to project costs.

No governor since CEQA passed has seemed more receptive to loosening its requirements than the current version of Jerry Brown, ironically taking a very different approach than he did in his first gubernatorial incarnation from 1975-83.

In a news conference last August, Brown allowed that “I’ve never seen a CEQA exemption I didn’t like.” Later he remarked that “CEQA reform is the Lord’s work.” It was no surprise, then, when developer allies in the Legislature quickly sought to push changes through.

Among the alterations attempted then and likely to return next year was an exclusion from CEQA for projects that already comply with local land-use plans previously certified as consistent with CEQA.

Brown’s turnaround on this law stems from his experience as mayor of Oakland from 1999 to 2007, a time when several projects he saw as bettering blighted areas of that city were delayed or stymied by challenges under CEQA.

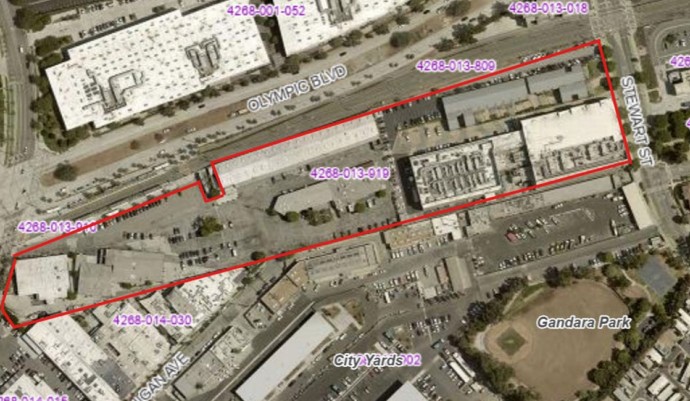

In his first year back as governor, Brown signed one bill fast-tracking legal review under CEQA for a proposed football stadium in downtown Los Angeles and another speeding up big projects (costing at least $100 million) that incorporate high environmental standards. But he pulled back on a push to exclude high-speed rail construction from CEQA. There has also been talk of excluding proposed water-transporting tunnels under the Sacramento-San Joaquin river delta.

The entire picture dismays environmental leaders and excites development interests. “It would be really devastating for California and probably the rest of the nation for the kind of precedent this would set,” Jena Price, legislative director of the Planning and Conservation League, told a reporter.

On the other side, the CEQA Working Group, a coalition of business, labor and affordable housing interests, claims that other laws like the Clean Air Act, the Endangered Species Act and a panoply of anti-smog laws make CEQA at least partially redundant, forcing developers to spend time and money going over similar sets of facts in excessive paperwork. This outfit maintains it wants to eliminate duplication and provide even wider environmental disclosure than CEQA now does.

“Duplicative and overlapping processes often result in lengthy project-permitting delays and uncertainty,” said Bill Allen, CEO of the Los Angeles County Economic Development Corp., in a letter to lawmakers.

But environmentalists point to a 2005 study by the nonpartisan Public Policy Institute of California indicating only one project in every 354 is ever delayed by CEQA-related actions.

They contend business interests don’t really want to modernize the landmark environmental law, they want to gut it and deprive the public of an opportunity to force changes that have often cut many stories out of high-rises and created numerous small wildlife preserves.

The strong arguments on both sides here make it obvious that changing CEQA should not happen in secrecy, but only with plenty of public input. But even at that, some softening of CEQA seems inevitable during the next legislative session.