Spend more than $30 million to pass a temporary tax increase proposition. See a governor put his entire political capital on the line to pass it, including airing countless television commercials featuring that man almost begging voters for a yes verdict. Threaten draconian cuts to schools and colleges that have already seen programs pared to the bone.

Result: The measure – last fall’s Proposition 30 – passes by a 55-45 percent margin, with every exit poll showing that, as Field Poll director Mark DiCamillo reported, “White non-Hispanics divided their votes evenly…but ethnic voters (Latinos, Asian-Americans and African Americans) collectively supported it by a 20-point margin, giving it its entire margin of victory.”

Another result: A sudden presumption that passing tax increases in California has become easy.

One product of this new assumption is a $2.2 billion per year tax increase proposition now being circulated primarily by liberal Democrats. This one – likely to be voted on in November 2014 – would add 2.5 cents per gallon to the already sky-high price of gasoline, tax alcoholic beverages varying amounts between a nickel and $1.65 per gallon and add a new levy on tobacco sales of 1.25 cents per individual cigarette.

The money would all be earmarked for higher education, with 80 percent going to the University of California and the Cal State system and the rest to community colleges.

One thing for sure about this proposal: If it gets the 807,615 valid voter signatures it needs to reach the ballot, you won’t see Gov. Jerry Brown staring into a television camera and imploring all Californians to vote yes.

For Brown himself would almost certainly share the ballot with this proposition, and he’s not likely to stake the outcome of what’s likely to be his final political campaign on the outcome of a tax proposition.

Yes, two tax measures did pass last fall: both Proposition 30 and the unrelated Proposition 39, which is now raising $1 billion yearly by closing some tax loopholes gifted to international corporations by ex-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger as part of a 2009 budget deal.

While the effort to pass 30 was difficult and in doubt until Election Night, many voters saw 39 as a no-brainer because it essentially taxes companies on their California profits, ending the previous shell game that allowed them to doctor their books by moving profits made here to other countries where taxes might be lower. Even at that, about 40 percent of voters still said no.

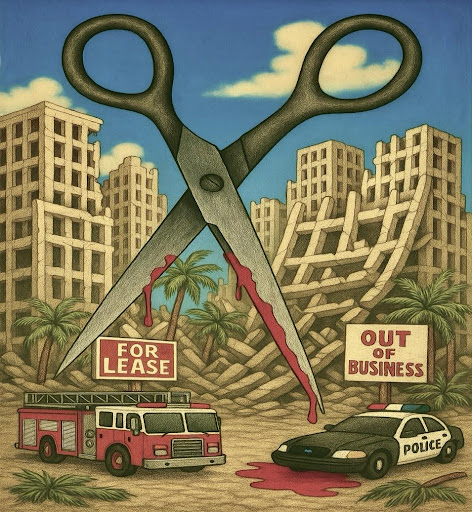

The fact those two measures passed at a time when state government had pled poverty for years and voters had seen roads deteriorate while many other services were cut does not mean passing more taxes will be easy.

Especially when the taxes proposed, as in the plan now circulating, would be permanent, unlike the levies of Proposition 30, which expire after four years unless voters okay an extension. The presumption behind 30 is that the economy will improve, eliminating the need for most of its taxes.

Schwarzenegger learned as recently as May 2009 how difficult it can be to pass even a temporary new tax, when his sales tax increase Proposition 1A lost by a 65-35 percent margin in a special election.

The makeup of the electorate has surely changed a bit since then, with more Latinos and Asian-Americans now on the rolls. But any such change does not come close to accounting for the huge difference between that outcome and the Proposition 30 win.

A sense of near panic over what might happen to schools, colleges, roads, water quality and many other state functions is about the only thing that can account for what amounts to a 20 percent swing in the vote between the two elections.

There is no longer any such sense, nor a great likelihood that any substantial political figure will even attempt to encourage one.

So the notion that passing yet another tax measure will be easy holds no water. Which suggests the newest tax increase effort is doomed long before it even qualifies for a vote.