There has been some dispute over whether the labor shortages California farmers reported over the last few years are real. It turns out they are very real, but that doesn’t quiet the skeptics.

“We are told that unless we allow criminals, illegal aliens, freedom to take American jobs, our agriculture will be destroyed,” wrote the conservative blogger Steve Frank, a former president of the California Republican Assembly, last year. “Like most other statements of the lamestream media, that is a downright lie.”

He used the fact that this state’s farm profits were up in 2011 – from $11.1 billion the previous year to $16.1 billion – to call the reported shortage “phony.” Those profit numbers came from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

But the USDA also reports on crop production (http://usda01.library.cornell.edu/usda/current/NoncFruiNu/NoncFruiNu-01-25-2013.txt), and some of those numbers tell a different story, while also implying that the added profits may have been a result of smaller supplies.

For example, California growers produced 1.5 million tons of raisin grapes last year, compared with 1.8 million in 2011, causing prices to increase while grape-harvesting expenses dropped.

Prices were also up for table grapes, from $306 per ton to $358, while the price of canned apricots went from $330 to $419 per ton, while production was down. So there’s more to the farm profit picture than just the bottom line. The price per pound or ton also counts for a lot. And both wholesale prices and profits rose last year, making it an outstanding one for agriculture.

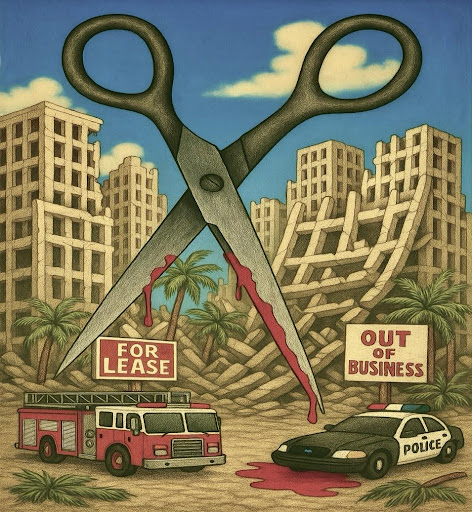

With 2011-12 a relatively wet winter, there was only one reason for production of anything to be down last year, with prices at or near peaks for almost all crops: A shortage of labor. This was caused in part by stricter enforcement of immigration laws, with the Obama administration already having deported more illegal immigrants than the George W. Bush administration did in its full eight years.

Farm labor problems persisted in 2012, although they’ve sometimes been hard to quantify. The Western Growers Association said last fall that its members were reporting 20 percent fewer laborers available than the year before. At the same time, the California Farm Bureau Federation put the shortage between 30 per cent and 40 percent of the workforce needed. Those numbers are not official, but the group said American workers were not taking the vacant jobs.

That was consistent with the results of an experiment conducted several years ago by Democratic U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein, who had every Employment Development Department office in the state list farm jobs as available. Fewer than 10 unemployed U.S. citizens applied for that work, even though it paid well over the state’s hourly minimum wage.

One Santa Barbara County farmer with crops as varied as lemons and strawberries reported that he had to leave some of his produce to rot in the field last summer and fall. Similar waste occurred in locales like Kern, Butte and Riverside counties, among others.

One reason: A large percentage of California fruit and vegetable pickers are illegal immigrants. Farm bureau organizations in other states report similar labor shortages. So farmers want any immigration changes coming from Washington, D.C. this year to include a guest worker program.

Agriculture organizations that usually support Republican politicians have pushed several years for a system allowing temporary hiring of foreign workers if employers cannot find U.S. citizens or legal residents to take the jobs they offer.

Organized labor has long opposed such a revival of the old Bracero program that allowed American employers to bring in unskilled foreign workers during and after World War II, the unions claiming it could deprive U.S. citizens of work.

But the nation’s largest labor group, the AFL-CIO, has now worked out a deal with the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and other business interests that would allow workers to be imported as needed to fill jobs that otherwise go unfilled. The proposed new visa would not specify a single employer for each worker, so that employers could no longer discipline migrant workers by threatening to have them deported if they’re not docile. It would also include wages above the federal minimum and require decent working conditions.

The Chamber also agreed to the unions’ idea of setting up a new government bureau to curtail work visas when unemployment rises to as-yet unspecified levels.

Two things are clear from all this: It’s highly likely that any major immigration change legislation passing Congress this year will have a guest worker component. And that this is happening mainly because of the labor shortages here and in other big farm states.