Reform of the California Environmental QualityAct has become a mantra for many California politicians over the last several years, all the way up to Gov. Jerry Brown, who found himself frustrated by CEQA at times during his years as mayor of Oakland.

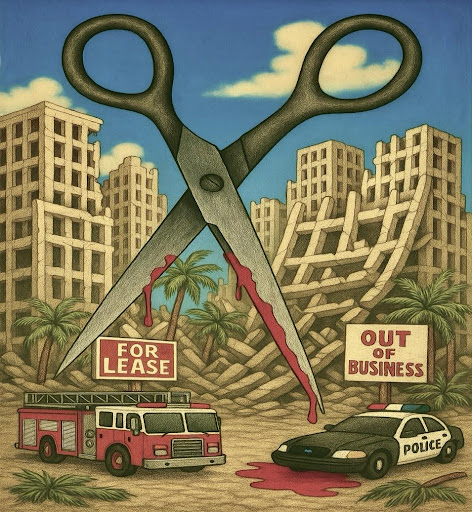

Butone person’s “reform” can sometimes be another’s disaster, and California may be about to find out what CEQA reform could really mean.

The arenas for this are two medium-sized Los Angeles area cities, Inglewood and Carson, both with ambitions to become somewhat like Arlington, Texas, the not-quite-Dallas home of the Dallas Cowboys football team.

Local officials in both cities, drooling over the potential of revenue that might come from hosting National Football League teams like the current St. Louis Rams, Oakland Raiders and San Diego Chargers, are going full steam ahead on two stadium proposals. Inglewood’s would be built by a development team headed by Rams owner Stan Kroenke, the other by a joint venture of the sometime rival Raiders and Chargers.

Even if both billion-dollar-plus stadia win eventual civic approvals (both are well on their way), it’s almost inconceivable both could be built. Their sites are only about 10 miles apart, both only a short hop from the already super-congested I-405 San Diego Freeway that runs past the Los Angeles International Airport. Who would make that choice, if it comes, and how that choice might be made are still unknowns.

These are the classic projects for which CEQA was designed. The 1970s-era act, signed by then-Gov. Ronald Reagan, requires a detailed environmental impact report (EIR) for almost all major projects. But none will be needed for either of these two gigantic projects because of a “reform” quietly introduced by the state Supreme Court last August, before Brown’s latest two appointees were seated.

As originally written, CEQA allowed exceptions to the EIR requirement if local voters approve ballot measures okaying projects. A 1996 vote, for example, allowed the San Francisco Giants’ AT&T Park to move forward without an EIR.

But the new court ruling allows city councils to outright adopt, with no popular vote, local initiatives that have already qualified for the ballot. Projects involved don’t need EIRs. Both big stadia now on the drawing boards employed this loophole (er, reform) and construction on one, or both, could begin as early as next winter with no input at all from local voters, other than those who signed petitions.

Both development groups spent a total of no more than $2.5 million to qualify the local initiatives in their relatively small cities, compared with potential costs of $100 million or more if they’d been forced to do EIRs.

Meanwhile, whatever air pollution, traffic, economic or other difficulties and benefits the presence of one or both stadia might mean for surrounding cities like Los Angeles, Torrance, Hermosa Beach, Manhattan Beach, El Segundo, Hawthorne and other points only slightly farther away will simply happen. No one will quantify the effects of the projects, either during the construction phase or as they draw huge crowds for football games, concerts and other events. Nor will the effects of other commercial and residential development tied to them be known ahead of time.

Yes, CEQA has been used many times by folks with not-in-my-backyard mentalities to stymie developments that might have been constructive. But CEQA has also prevented many potentially destructive projects, and mitigated potential damage from thousands of other projects that did get built, but somewhat differently than initially proposed.

Few would argue that AT&T Park has had a mostly positive influence on its Mission Bay area of San Francisco, but that project was fully debated before the voters before it was built.

Not so for these new stadia, thanks to the state’s highest court.

Over more than 40 years, CEQA has become a tradition, like it or not. What’s going on now may turn into a classic example of what can happen when people throw out a tradition. Often they discover why that tradition became established in the first place.

One thing for sure: Californians will soon know the full effects, good or bad, of the change the state Supreme Court made to the CEQA tradition. The hope here is that it’s all positive, but no one really knows, and that may lead to many unforeseen problems.