Gov. Jerry Brown has never professed to be the model of political or ideological consistency. In fact, he’s a decades-long advocate of the “canoe theory” of politics, which goes like this: You paddle a little to the left and you paddle a little to the right, and you keep going straight down the middle of the steam.”

You also keep all sides guessing a lot of the time and you make sure opponents of some of your policies are allies on others.

So the governor who once proclaimed that “small is beautiful” and announced an “era of limits” for California apparently has no stomach for limits on huge developments.

That’s the meaning of the agreements he made with legislators to exempt some of the most significant building projects on California drawing boards from many environmental regulations. These deals were part of the horse-trading that led to easy passage of the new state budget.

Brown’s press release on the budget, of course, made no mention of such deals, which also exempt the project-enabling bills from thorough legislative hearings because like the developments they promote, they are fast-tracked.

Yes, the same governor who demands that Californians cut gasoline use by 50 percent before 2050 and who is forcing electric companies to draw the bulk of their energy from renewable sources by 2030 has no qualms about facilitating a $200 million high-rise development in the Hollywood district of Los Angeles or the Golden State Warriors’ proposed new arena in the Mission Bay area of San Francisco, near the Giants’ AT&T Park.

This is the same governor who has not opposed changes in the California Environmental Quality Act, known as CEQA, that allow developers to qualify initiatives okaying their projects for local ballots and then let city councils adopt those initiatives without a public vote or debate.

That’s what happened in both Inglewood and Carson, medium-sized Los Angeles County cities where okays for competing 70,000-seat National Football League stadium plans came like greased lightning last winter, with no public input. Brown previously had quickly approved the Legislature’s easing of regulations on another, now inactive, NFL stadium plan for downtown Los Angeles.

Brown’s collusion in efforts by developers and their pet legislators to ease the path of massive, neighborhood-changing projects stems from his late 20th Century years as mayor of Oakland, where state regulations stymied or delayed several housing and school projects he wanted.

It was like a rude awakening to the real world for the onetime seminarian.

But that’s no justification for depriving citizens of their right to input on projects, as Brown has now done several times, all while trying to maintain an image as America’s most environmentally-conscious governor.

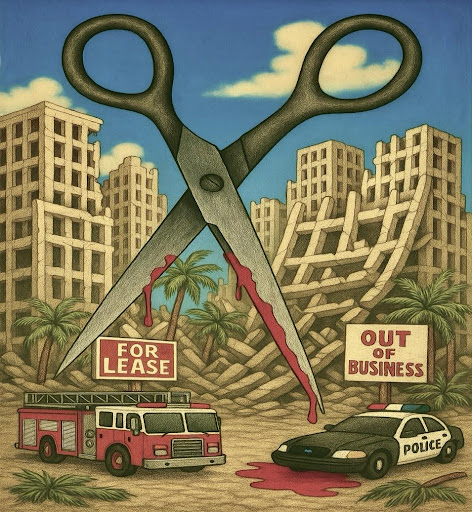

For the 45-year-old CEQA, which remains the same law today that onetime Gov. Ronald Reagan originally signed, the deals Brown has agreed to amount to a “death of a thousand cuts,” says one official of the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Essentially, the exemptions for the largest projects now planned for California, the ones with the most potential environmental impacts, mean that the very wealthy can skirt the law by lobbying Brown and local legislators and city council members (read: making campaign donations), while homebuilders and others must live within the regulations.

The latest ones also mean that residents of Hollywood and San Diego’s Mission Bay, like people in cities like Hermosa Beach, Lawndale, Torrance and Manhattan Beach who are certain to affected by whichever new stadium goes up near the already clogged I-405 San Diego Freeway, will have little to say about their futures.

If this is what Brown really meant when he campaigned in 2010 on a promise to devolve more government authority to locals and away from the state, it will surely go down as one of the least green and least positive legacies of his long political career.