By Susan Cloke

Frank Gehry likes to say, “You know, I’m 88.” He was born in Toronto, Canada in 1929. As one of only 30 Jewish families in town at that time, he often found himself called names and physically attacked.

Gehry is now a “starchitect” – a label given to the current group of world famous architects who have variously expressed the culture, angst and beauty of our time through their architecture. It is a label he does not seek. “I’m still in my head the outsider and I feel comfortable there. I like it there,” says Gehry.

Santa Monicans will have seen his new house, under construction on Adelaide, built for his wife Berta and designed by their son Sam with a lot of kibitzing from Frank. The front form holds one bedroom, a living room, a dining room and a family room. The back form holds two guest rooms and a small caretaker’s apartment, a music room and the garage. The house boasts an impressive use of geothermal energy. Gehry applauds the environmental benefits but deplores the cost. He thinks as costs decrease the use of geothermal energy will become mainstream.

“The chain link in the front is only temporary,” said Gehry – a tongue-in-cheek reference to his house on Washington and 22nd in Santa Monica. Built in the 1970s, his use of chain link and other ubiquitous materials to build this “inside/outside” house made him both revered and scorned.

On a banner sunshine-into-dusk day, with the Pacific sparkling in the background, people gathered to hear the Architecture Critic Joseph Giovannini interview Frank Gehry. The Los Angeles Review of Books (LARB) sponsored event was held in the home of architect and painter Susan Morse.

Giovannini introduced Gehry saying, “He is a world historical figure.” Giovannini’s introduction is supported by Gehry’s work. A partial list includes the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain; the Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum at the University of Minnesota; the Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College, in Annandale-on-Hudson, NY; the Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, CA; Opus Residential Tower in Hong Kong; Foundation Louis Vuitton in Paris, France: and the Boulez Hall in Berlin, Germany.

Gehry’s interest is currently focused on the L.A. River Project. Asked by Los Angeles Mayor Garcetti, Gehry is working, pro bono, on a study of the river. “The thrust of what has happened so far is habitat and recreation,” said Gehry.

“The ideal,” Gehry explained, “is to divert water during storms and return it to the river or clean it and return it to the aquifer.”

Gehry wanted to understand the communities along the 51 miles of the L.A. River. As part of this work he prepared an index of public health issues, specifically through South L.A. to where the river meets the ocean in Long Beach. Gehry found staggering numbers recording high health risks of diseases that public health officials correlate with limited open space and few recreational activities.

Gehry studied reports from the Army Corps of Engineers to gain understanding of the engineering challenges of the L.A. River Project.

The Corps now also supports habitat and restoration of the L.A. River and ties the project to environmental quality. Tension and conflict in the initiative comes with locating available land, which is difficult in some areas, and flooding which is always dangerous. “Hard not to get stuck,” Gehry mused, “Where to go?”

Gehry is turning his attention to the Boyle Heights part of the L.A. River thinking, “If you could build a park it would connect the City.”

Continuing his interest in education he is contributing to a Michelle Obama program for Arts in the Schools. “Melissa Shriver runs our program and we now have 14 schools we fund where we bring arts to the classroom. It is similar to my work in the 70s on a program directed by my sister, Noreen Gehry Nelson, called Design Based Learning.”

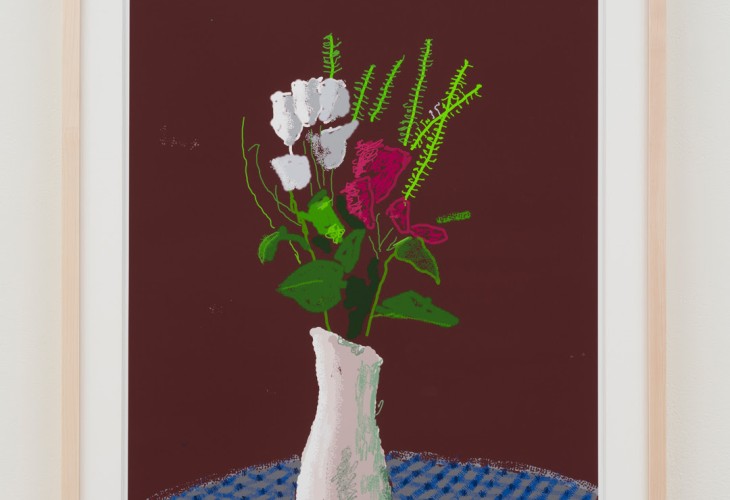

Gehry describes one class where “David Hockney came to Menlo Park. He brought vases and flowers, arranged them, drew on the computer and projected the drawings on a wall. 60 percent of the children in the class were homeless. We gave them each a computer and they then made their own drawings which are now on display at Zuckerberg’s office.” (Zuckerberg funded this project.)

From schools in California to music in Germany, Gehry continues to use his status and his art to create buildings and to work for world changing communities. In Berlin, working with Daniel Barenboim, Gehry designed the Pierre Boulez Saal where young Arab and Israeli musicians train together with the combined idea of creating music and creating hope for the future of the Middle East.

The journalist Joseph Morgenstern, writing for the New York Times in 1982, said about Gehry, “Even in California, where idiosyncrasy is a mass movement, Frank O. Gehry is in a class by himself. He is the most important architect in the state, indeed in the West.” That was 1982. He is now one of the most important architects in the world. Gehry’s work expands the definition of starchitect to include a person who uses skill, knowledge and position to make a more interesting, more fun and safer world.