[We wrote this article 6.5 years ago. Today, the issues it raises continue to bedevil the city, and with more impact than ever. The results of the pandemic and the State-imposed requirement to provide building permits for nearly 9,000 apartments and dwellings within the next eight years call for swift and thorough action, by our city government and residents, to help solve the challenges outlined below. The article has been edited for length and added recent data.]

Two weeks ago one of our SM a.r.t. members was forced out of his apartment by a fire resulting from the explosion of a faulty transformer. The response by the Fire Department was exemplary, but for many of us, this incident reinforced the sense of an aging, and indeed tottering infrastructure in our city. Too often we hear of transformer explosions, blackouts or brownouts, sudden drops in water pressure, and other events that make us wonder if the buildings, roads, and power supplies needed for the operation of our city are failing to keep up.

It is an indisputable fact that increased development requires increased infrastructure. A large new project will impose demands on the city’s road network, water system, sewage network, fire department, electrical networks and many other services Santa Monica provides to residents and visitors. Do we have enough capacity to support the many new projects in the pipeline?

The city has made an effort to answer this question. The main planning document for our city is the 2010 Land Use and Circulation Element. This plan guides planning decisions in the city all the way out to the year 2030. The LUCE plan estimates that by 2030 Santa Monica would have 4,900 new dwelling units. How did the LUCE plan arrive at this number? It uses population figures developed by two California government organizations, and those–in part– are forecasts based on historical trends, and not on what the plan itself actually allows to be built in the city. This is an important figure to get right, because the number of people living here, among other things, will help determine the amount of infrastructure improvements the city will need.

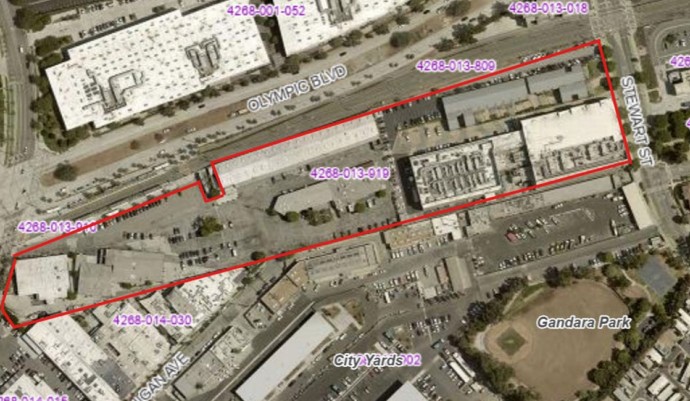

In a report packed tight with data, back in 2012, our then-colleague Armen Melkonians noted the number of dwellings forecast by the LUCE plan, and compared them to the number that would be allowed to be built under the same plan. Armen found that just for the Bergamot area alone, the city forecast an increase of about 1,300 dwelling units, but the plan actually allowed an increase of about 7,000 units. That’s a huge difference in water, sewage, electricity and fire services right there, and that is just one part of the city.

Which estimate should we use–the one based on historical trends, or the one based on what the plan actually allows? Every large project up for approval has relied on the city’s numbers, so this is an important question. Will developers build to the maximum size allowed by the code, or will they stop short? For the answer, take a look around the city and notice that developers have been building to the maximum and beyond.

The city has a goal of water self-sufficiency (from its own wells and other sources) within six years. This is a worthy plan, because the city’s own groundwater supplies are more reliable than water purchased from the state (which is susceptible to droughts and other events). One problem is that the city’s calculations for the amount of water needed are based on the same historical-trend population estimates mentioned earlier, and not on what our own zoning code actually allows, which–potentially– could result in far greater water consumption. Another problem is that we do not have exclusive rights to the aquifer in which our wells our located. The city of Los Angeles, for example, recently commissioned a study to see how much water it could extract for its own use from this very same source (at the Venice Reservoir site, near Palms). So it is unclear how much water Santa Monica could eventually get from its own existing wells, and from the new ones it is planning to build, even as its water conservation efforts (including the use of recycled water) achieve truly remarkable results. If we cannot meet all our water needs, we will continue to purchase water from the MWD to make up the difference, at prices influenced by outside factors (such as drought). In this scenario, the more development that takes place, the more water will be purchased, and at increasingly higher prices and more questionable reliability.

Another important issue is the ability of the Fire Department to provide speedy service in areas that are becoming increasingly congested by the construction of large projects. Our Fire Department is staffed by expert and extremely competent people who achieve wonderful results (in 2008, the average response time was 4 minutes for emergencies, and 5 minutes for non-emergency calls), and they must surely be thinking hard about how to deal with this problem. But it is unclear whether the Fire Department can evaluate the total traffic impact of multiple projects coming on-line within a short amount of time. Reasonable people may differ on the cumulative impact these projects may have on Fire Department response times, but if earlier estimates are correct there will be no choice but to expand the Fire Department’s resources (and water availability, since those two are connected), and those must be planned in advance, before–and not after–large projects are approved. As in so many other city matters, it is better to plan ahead–transparently–than to play catch-up when it’s late.

In all cases we must estimate the amount of water–and other infrastructure needs such as roadwork, electricity, sewage, and fire services–accordingly, and plan for the real impact of those costs on residents. When a project is evaluated, the full number of other projects in the pipeline must be taken into account, and not only some (as occurred with the recently defeated Plaza at Santa Monica project). Will completion of a very large project result in increased water costs for residents throughout the city? It is only fair to let people know the answer. For the Fire Department, any single project may not have much impact on overall response times, but 30 projects completed in a short period could present a very different picture. As more projects get completed, the room for errors in infrastructure planning matters gets smaller.

Without a comprehensive and realistic plan, our goose, as the saying goes, will be cooked, and the ever-expanding infrastructure costs will impose an increasingly heavy burden on our residents and businesses. The denser the city gets, the less room we have for mistakes in planning.

One explanation we often hear for the approval of large projects centers around the community benefits these projects would provide, but little is heard of the infrastructure burdens imposed by these same projects. Swimming vigorously in our city’s development waters is a large and hungry shark called the Law of Unintended Consequences. It would be an ironic tragedy if the very people intended to benefit from these projects were harmed, instead, by the rising tide of infrastructure costs that may, eventually, engulf the city.

by Daniel Jansenson, Architect, Building & Fire-Life Safety Commissioner for SMa.r.t. (Santa Monica Architects for a Responsible Tomorrow)

Ron Goldman, Architect FAIA; Dan Jansenson, Architect, Building & Fire-Life Safety Commissioner; Mario Fonda-Bonardi AIA, Planning Commissioner; Robert H. Taylor, Architect AIA: Thane Roberts, Architect; Sam Tolkin, Architect; Marc Verville accountant ret.; Michael Jolly, AIRCRE