Quartz countertops are super popular because they’re tough and can handle stains, scratches, and heat. But there’s a big problem: the people who make these countertops are getting sick and even dying from lung diseases when they’re still young.

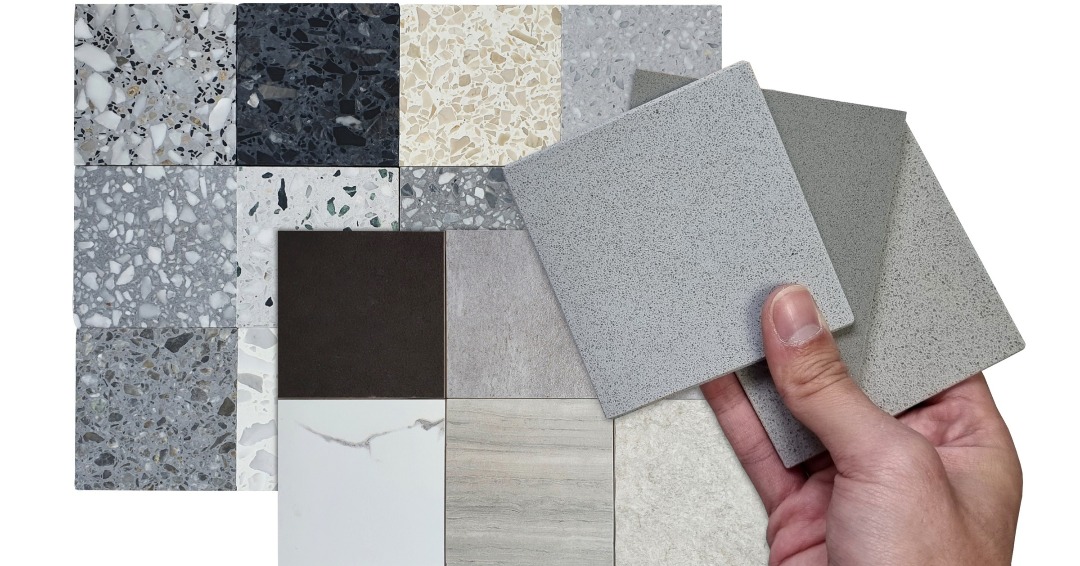

Engineered quartz countertops are created by mixing crushed quartz stone with resin and dyes, giving them a stunning appearance that many people love. However, it’s crucial to know that these countertops have a lot more silica than countertops made from natural materials like granite or marble or even synthetic materials like plastic laminate or solid surfacing (made from minerals like marble mixed with acrylic, resins, and pigments).

The high silica content in quartz countertops can be extremely harmful to the health of those who work with them. Many of these workers are low-income immigrants who often don’t have health insurance. They are typically employed in small workshops in the Los Angeles area that may have poor working conditions and lack safety certifications. These slabs are in extremely widespread use, and it is time for Santa Monica to consider banning this product.

In the past decade, doctors discovered that workers cutting and fabricating countertops from these materials often develop a serious lung disease called silicosis, sometimes referred to as “black lung” in the context of coal mining—an illness caused by breathing in tiny pieces of silica. Silicosis makes you cough a lot, get out of breath, feel tired, lose weight, and it scars your lungs. It may increase your risk of developing serious conditions such as lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and kidney disease. A large percentage of victims die from the illness.

California—and Los Angeles County in particular—is the epicenter of this problem in the U.S. A recent study conducted by researchers from the University of California, San Francisco, UCLA, and the California Department of Public Health revealed that between 2019 and 2022, 52 engineered stone workers in California were diagnosed with silicosis; 51 of them were Latino immigrants. Among these patients, 20 had advanced-stage silicosis, and tragically, 10 of them have passed away. The average age of these patients was 45, and they had worked in the stone industry for about 15 years. Most of these cases are concentrated in the Los Angeles area. But the problem is not confined to these individuals.

A co-author of the study warned that without intervention, we may witness hundreds if not thousands, more cases over the next decade because silicosis takes years to develop. Other experts are also sounding the alarm, saying that if we don’t act fast, we could see many more cases of silicosis in the coming years. They want better protection for workers, quicker diagnosis of the disease, strong safety measures in shops where countertop fabricators work, and maybe even an outright ban on quartz countertops.

The issue has been getting attention in the press, most recently last week in the Los Angeles Times, as well as LAist, Fast Company, and other publications. Cal/OSHA has taken notice. It recently began working on an emergency silica rule and launched a special enforcement program to address this problem. And the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors has instructed the director of Public Health to prepare a report outlining options for banning the sale, fabrication, and installation of silica-based stone countertops in the county.

All of these measures, while noteworthy, will take a long time to produce real, effective, life-saving action. Reports, studies, and committees will do their thing, but in the meantime, demand for these countertops continues to grow, including in many new projects under construction in Santa Monica, and workers with few protections continue to get sick.

An example of such a worker is the case described in the recent study published in JAMA Internal Medicine of Leobardo Segura-Meza, a Mexican immigrant who arrived in the U.S. in 2012 and found work as a stone worker in Los Angeles. Despite taking precautions like wearing a mask and using tools to reduce dust exposure, he was diagnosed with silicosis at the age of 27 in February 2022. Since then, he has relied on an oxygen tank, can no longer provide for his wife and three children, and is on a waiting list for a lung transplant. He recently told the California OSH Safety Board that two of his former co-workers had died waiting for transplants and that he’s worried about running out of time before a lung transplant becomes available for him.

Santa Monica can do its part to help save the health and lives of these stone workers. Our city can take concrete steps to make sure these workers stay safe, and one key option is to ban high-silica materials in projects built within city limits. This would significantly reduce the health risks these workers face. The city can enact an emergency ordinance requiring planning officials to prohibit these materials when they approve building permits, force builders to certify that these materials are not being used, and require code-enforcement officials to visit construction sites to make sure the ban is carried out.

The city will encounter stiff opposition from industry supporters who fear job losses and economic problems if high-silica materials, such as quartz countertops, are banned. They have already argued that better safety measures and equipment can protect workers without the need for a ban. However, as Cal/OSHA has noted, most employers in this industry, and particularly small businesses, are unable or unwilling to use well-recognized engineering and work practices that could help reduce illness due to silicosis, a fact that was evident during a special program to help reduce this problem in 2019 and 2020, during which the agency observed widespread non-compliance with the rules.

New rules are coming both in L.A. County and the State of California. The process of passing those rules will take considerable time. But in the meantime, countertop workers with few resources and little health insurance continue to get sick and even die from the cutting, sawing, and sanding of these materials. Other, far less damaging countertop materials, just as beautiful and durable, are widely available. The city of Santa Monica has shown that it can act nimbly when the occasion calls for it.

The occasion is calling. The city must act now.

Daniel Jansenson, Architect, Building and Fire-Life Safety Commission, for S.M.art (Santa Monica Architects for a Responsible Tomorrow).

Thane Roberts, Architect, Robert H. Taylor AIA; Dan Jansenson, Architect, Building and Fire-Life Safety Commission; Samuel Tolkin Architect, Planning Commissioner; Mario Fonda-Bonardi, AIA; Michael Jolly, AIR CRE.