Earlier this week, in the dark pre-dawn hours, a pair of thugs covered in masks and hoodies burst into the lobby of the 23-unit apartment building where I live, ran down the hallway, and quickly wrenched open the building’s mailbox cabinet. They looted the mailboxes and, on their way out, encountered a resident whom they promptly attacked with fists and burglary tools. The resident fell injured to the floor, and the assailants fled with the stolen mail in a bag, their escape captured on video. The police were called and arrived within minutes. The thugs were gone.

As may be imagined, this event has caused the building’s 50-odd residents–including elderly widows and young families– to re-evaluate the safety equation underlying daily life. In past years, as crime levels have increased, accounts of criminal events always seemed to be happening elsewhere. In a different city. In another part of town. On a different street. Up the block. To someone else. Now, the rising tide is at our doorstep. It is no longer outside the building’s front doors–it’s right at each person’s own unit. That’s a profound change in perception, and we are soon to see the results in our building.

Those who keep abreast of the city’s crime reports, whether through traditional media outlets or official announcements, recognize that this issue transcends the boundaries of Santa Monica. It is a pervasive problem, affecting communities regionally, statewide, and even nationally. Despite these broader implications, we look to our local leaders to come up with effective solutions. While commendable efforts have been made, such as the expansion of the police force, heightened patrols, and the engagement of private security, an increasing number of residents are directly experiencing the effects of crime, which inexorably chips away at our sense of safety.

This erosion of the feeling of safety is, in part, fueled by the amplification of crime-related content on social media platforms. Daily inundation with reports of assaults, burglaries, thefts, and robberies fosters an atmosphere of pervasive anxiety and apprehension regarding personal safety, irrespective of whether one has been personally victimized.

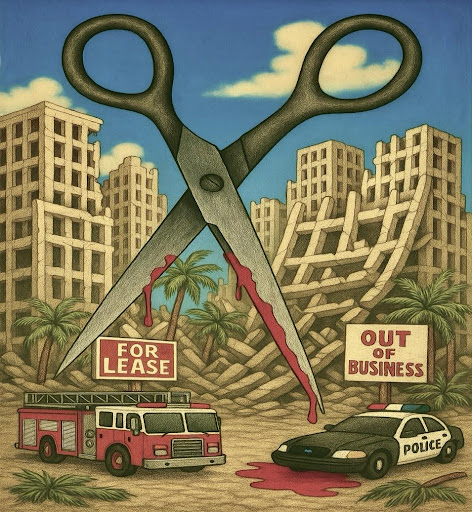

Increasingly, however, the appreciable decline in the sense of safety is substantiated by the escalating incidence of actual criminal activity on our streets and within private properties, despite assurances to the contrary from law enforcement and city authorities. With each passing day, an increasing number of residents either directly experience or have firsthand knowledge of serious criminal acts. Whether perception shapes reality or reality shapes perception, a prevailing sense of fear and vulnerability is taking root within our community.

More needs to be done, specifically at the City Council level. While many Council members, including the current Mayor, have demonstrated commendable diligence in addressing the issue of crime, there are some members who–to put it delicately–have been less than enthusiastic supporters of the effort. Whether stemming from ideological biases or a distorted understanding fueled by antagonism towards law enforcement (an antipathy, we note, that is rooted in poor behavior by some police officers in the past), this attitude must change if we want a safer city for everyone. But there’s another reason for such a change.

Recent investments in public infrastructure, such as public transit, libraries, and recreational parks, are being undermined by the visible presence of criminal activity. There are people in this city who will avoid using their bicycles, not only because of increasingly dangerous, unchecked behavior by some drivers (and some cyclists) but also because of the prospect of losing their bicycle to theft, either parked at home or their destination, is a real deterrent (this writer is one). There are parents who will no longer take their children to parks because of the danger posed by used needles left discarded on the ground. There are plenty of people who have stopped taking public transportation because of the fear of assaults on buses, trains, and stations–a fear rooted in reality.

The effects of crime have even crept, consciously or not, into our city’s urban design, with new projects featuring green open spaces that are barred from public view, raised high up, well above street level, to protect the users living in those projects and thus creating, in the process, inhospitable, fortress-like conditions at street level for passing pedestrians. The mere concept of vibrant street life has started to fade from the actual designs (if not from developers’ brochures). It is rarely–if ever–mentioned by city authorities, including boards and commissions, with the power to review these projects.

Solutions need not rely solely on costly defensive infrastructure; simple yet effective measures, improved street lighting, and the implementation of monitored surveillance systems have been proven to significantly deter criminal activity (Criminology and Public Policy street lighting study and Springer.com study on proactive CCTV monitoring). The city can also do more to help create and support Neighborhood Watch organizations, including a “neighborhood watch czar” at City Hall. There are many creative measures that can be taken to help with the problem.

Every city has a hierarchy of needs, not unlike the one proposed by Abraham Maslow for individuals. At the bottom of the hierarchy–that is, at the base, needed for all other needs to be realized (such as love, belonging, esteem, and self-realization)–Maslow’s concept includes safety. It is a basic building block for everything else. Reducing crime is a core obligation of the city. A city that cannot take care of the basics cannot solve other problems and cannot improve its residents’ lives.

Back to the event in my building, later on the morning of the attack, I met with the resident who was assaulted. His head was covered in bruises, lacerations, and lumps from the beating. As he hurriedly ushered his children off to school, the gravity of the situation became palpable–those little children knew that their father was assaulted on their very own doorstep.

What kind of life does that promise them?

Daniel Jansenson, Architect, Building and Fire-Life Safety Commission.

Santa Monica Architects for a Responsible Tomorrow: Thane Roberts, Architect; Mario Fonda-Bonardi AIA; Robert H. Taylor AIA, Architect; Dan Jansenson, Architect & Building and Fire-Life Safety Commission; Samuel Tolkin Architect & Planning Commissioner; Michael Jolly, AIR-CRE; Marie Standing, Jack Hillbrand AIA