By Ben Wong

When it comes to sports, Santa Monica High School basketball coach James Hecht and art teacher Amy Bouse are on opposite ends of the spectrum.

Hecht, who also teaches algebra at Samohi, is a pillar in the athletic program. He has coached basketball at his alma mater for 23 years and believes that the gym, like the classroom, is a place that develops and reveals character.

Bouse is not a sports fan. She doesn’t quite understand how people can blindly pledge allegiance to a group of athletes they don’t know or why anyone would yell at a TV.

But when you talk to either educator about their former pupil, current Gonzaga shooting guard Jordan Mathews, Hecht and Bouse gush pride and admiration. To them, Mathews’ integrity, intelligence and work ethic are what make him special. It’s why they’ll both turn their attention to Glendale Monday to watch Mathews in Gonzaga’s first national championship chance.

Hecht knew Mathews would play Division I basketball since the then-junior transfer canned a game winner, the first of many, shortly after his arrival.

“That’s when I knew, it was maybe his third game for us and a summer league game,” Hecht said. “He wanted the ball. He wants to lead the team and he wants the ball in his hands. He’s a leader.”

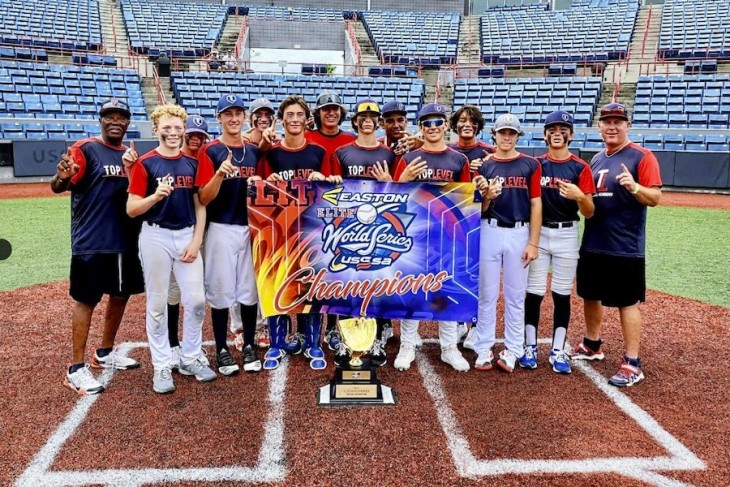

Mathews established himself as a top-level player, winning MVP of the Ocean League twice and leading Samohi to a CIF Southern California Division I championship as a senior. His success, Hecht says, is due to his intense commitment to whatever task is in front of him.

“He’s just a gamer,” Hecht said. “He always would want to come in and put in the extra time. I know his father used to get him up before school, and go to the gym and get shots up. He had a blueprint and he followed it and I think the results speak for themselves.”

This drive to compete and complete does not stop when Mathews leaves the court.

Bouse says that initially, Mathews resisted her painting class. But his hesitation with the arts switched when Bouse took an interest in his love of basketball and began attending games she knew little about. In class, after game days, they’d discuss strategies and the mental aspects of the prior day’s contest while also analyzing art.

“We talked a lot about how the art-making process is similar to sports in terms of discipline, luck, and having good intentions without being invested in the result,” Bouse said.

Mathews, who Bouse calls “an exceptional person,” began leading art critiques in front of the class and enjoying the methodical process of artistic creation.

“He likes learning things. He’s definitely got an active mind. He thinks about things really deeply and it helped me see sports and athletes in a new way.” Bouse said.

Bouse said she’s been in the arts and humanities her whole life and sometimes struggles to understand why sports gets the kind of attention and money it does.

“Socially, it’s kind of a thorn to have these people who have tremendous ability and discipline and strength and the right body for whatever it is that they are engineered to do to be so richly rewarded for something,” she said. “Because it doesn’t seem always like there’s a great contribution to the greater society.”

But in Mathews, she found a contributor, and an athlete to care about.

“I don’t really understand how someone can watch a game and say, ‘We won!’ You didn’t do anything, you’re just part of the audience,” she said. “But, I felt like it was important to Jordan that I was at the games and I felt like a part of it. That helped me understand the feelings that people have for their team.”

“For me, Jordan was humanizing a whole set of people that in my world, are easy to demonize for people in my realm of the world,” Bouse said.

Mathews’ most recent challenge brought his two worlds of basketball and education together. In order to transfer to Gonzaga for his final season, he had to complete his undergraduate legal studies degree at Cal Berkeley last summer. He took six classes in 12 weeks, something his school counselor told him was impossible.

“If he says he’s going to do something, he feels a strong obligation and commitment to doing it. It doesn’t surprise me that he could accomplish that,” Bouse said. “I think he understands that how you spend your minutes determines how you spend your days. He’s willing to make those long-term commitments.”

Hecht relays the similarities between effort on the field and in the classroom to his players, students and fellow teachers. Mathews, whose father is a basketball coach and mother is a teacher, is a useful example.

“I’m very proud of him,” Hecht said. You think about a Santa Monica High School student and you want them to have the best experience they could possibly have. Academically, socially, and you want them to feel connected to something, whether that’s the sports or the arts, and he was such a well-rounded individual here.”

When Mathews takes the court Monday, he will bring with him the early-morning shooting sessions at Samohi, grit fortified by his academic perseverance and a quick but deep mind.

Hecht will gather his two sons, a 10- and a 12-year-old who worship Samohi basketball, and get ready to celebrate Mathews’ every move.

Bouse, who watches every Gonzaga game, will reflect on a conversation she had with Mathews at the end of his time in art class.

“He said to me, ‘If you had told me three months ago that I’d be in a painting class and enjoy it, I never would have believed you.’ I told him, ‘If you told me I was going to go see a basketball game, and enjoy it, I never would have believed you either,” she said with a laugh.

Nearly five years after she encouraged Matthews to pick up a paintbrush, she will be watching him play on one of collegiate athletics’ greatest stages, grateful for the lessons of her former student.