Santa Monica operates under a council–manager system where an elected council establishes policies but delegates day-to-day operations to a professional city manager. While meant to ensure stability, this setup has resulted in staff-driven outcomes, weak oversight, and reduced accountability.

Staff-Driven Outcomes

Council members, who serve part-time and often lack detailed expertise, depend heavily on staff. This dynamic repeats frequently:

- Budget Crises and Autonomy: During the COVID-19 pandemic, then-City Manager Rick Cole resigned amid disputes over deep budget cuts. The council’s limited role in scrutinizing compensation and severance showed how managerial decisions outpaced political oversight.

- Major Civic Assets: Decisions regarding the Santa Monica Airport and Civic Auditorium have been largely shaped by staff feasibility studies, legal assessments, and exclusive negotiating agreements with developers. The council typically receives staff-driven recommendations late in the process, effectively rubber-stamping them.

- Perceived Priorities and Outside Interests: Residents frequently criticize staff and council for prioritizing legal risk, developer proposals, and narrow financial considerations over bold public goals. This fuels the perception that city hall caters more to outside developers’ interests than to residents’ needs. The disputes over the airport and Civic projects reflect this accountability gap.

Staff and professional administrators generally seek stability, but the complexity of budgets, planning, and legal obligations grants them operational control. Without strong oversight or a mayoral system with direct accountability, elected officials risk acting as intermediaries rather than true leaders.

The Uller Scandal and Fiscal Reckoning

The Eric Uller scandal exposed the dangers of weak oversight. For decades, warnings about Uller’s abuse of children in police-linked programs were ignored. The aftermath has been devastating:

- Settlements: Santa Monica has paid $229 million in Uller-related claims, with more than 180 cases still pending.

- Deficit: The city projects $473.5 million in revenue against $484.3 million in expenses, resulting in a $10.8 million deficit.

- Public Trust: The scandal damaged the city’s reputation, deepening fiscal and civic challenges.

Broader Economic Headwinds

Beyond Uller, broader shifts are eroding revenues:

- Retail Decline: Third Street Promenade has lost over a third of its foot traffic since 2019.

- Anchor Departures: Nordstrom closed its Santa Monica Place store.

- Tourism Losses: Post-pandemic changes cut into hotel and sales tax revenues.

- Coupled with rising pension obligations and union costs, these factors threaten fiscal stability.

Real Bankruptcy and Outsourcing Risks

If left unchecked, Santa Monica could face a similar fate as Stockton, California, which filed for bankruptcy in 2012 and outsourced core services like trash collection and vehicle maintenance. Once bankruptcy courts take control, decisions shift to outside professionals, weakening local democratic authority.

Santa Monica risks similar restructuring if it delays reforms. Addressing pension costs, union contracts, and structural deficits now is far better than facing forced external management.

Options to Consider for Structural Reform

To prevent decline, Santa Monica must rethink its governance structure:

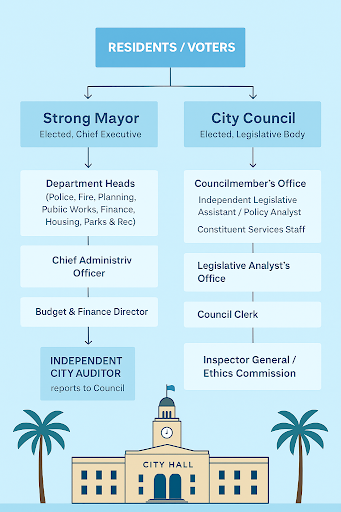

1. Charter Reform: Consider a hybrid strong mayor system. In this model, a directly elected mayor would serve as the chief executive with authority over departments, budgets, and operations. Meanwhile, an empowered city council would retain legislative powers, land-use authority, and the ability to adopt budgets. Each council member would have independent staff and offices, allowing them to evaluate proposals without relying solely on city staff. This hybrid balances executive accountability with legislative oversight, reducing the risk of bureaucratic dominance or executive overreach.

2. Checks and Balances: Pair executive power with oversight tools such as independent audits, a nonpartisan CFO, a strong auditor, and strict transparency rules.

3. Empowered Council: Give council members their own offices and staff to lessen dependence on city staff and enable independent analysis of developer deals, budgets, and contracts.

4. Incremental Testing: Use a charter commission to develop and test hybrid structures through voter approval.

The Democratic Question

Santa Monica faces fundamental choices:

Continue with a council–manager model, where unelected staff and external forces often dominate decision-making, and council members remain intermediaries.

Consider adopting a hybrid strong mayor system, where voters elect an accountable executive, but councilmembers retain independent authority to legislate and oversee. This approach is about more than efficiency; it’s about democracy. Should residents’ voices be filtered through a council that often cedes power to staff and outside interests, or be balanced with a mayor directly accountable to voters?

Conclusion

Santa Monica prides itself on transparency and progressive values. Yet, its current structure buries major decisions in staff reports, weakens accountability, and diminishes leadership. The revolving door of city managers worsens this instability.

If Santa Monica aims to tackle homelessness, crime, fiscal instability, and preserve its civic heritage, it must now pursue structural reform. Delaying action risks not just inefficiency but a systemic collapse and possible bankruptcy.

Michael Jolly for SMa.r.t.

Santa Monica Architects for a Responsible Tomorrow

Samuel Tolkin, Architect & Planning Commissioner; Thane Roberts, Architect; Mario Fonda-Bonardi AIA, Architect; Robert H. Taylor AIA, Architect; Dan Jansenson, Architect & Building and Fire-Life Safety Commission; Michael Jolly, AIRCRE; Jack Hillbrand AIA, Landmarks Commission Architect; Matt Hoefler NCARB, Architect.