How Solo Living Is Shrinking the Functional City

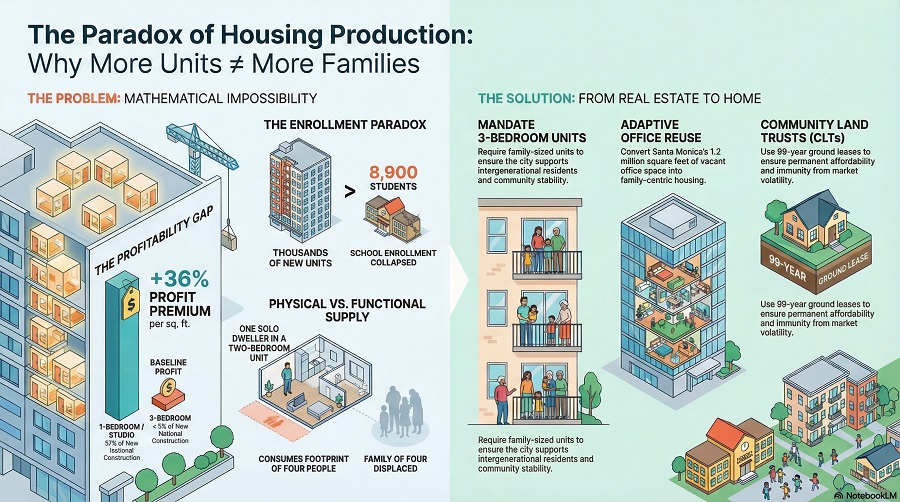

SMa.r.t.’s article last month referred to Santa Monica’s collapsed school enrollment of 8,900 students. The figure arrives despite the addition of thousands of new apartment units over the past decade. This paradox defies the conventional logic of housing policy. The explanation lies not entirely in population decline but includes a new shift in our housing stock due to solo dweller occupancies. This demographic transformation has quietly converted a housing crisis into what can only be described as a mathematical impossibility.

The distinction between physical housing stock and functional supply is critical to understanding what has happened. When a single person occupies a two-bedroom unit—a common occurrence as solo dwellers outbid families for larger spaces—that unit consumes the same physical footprint that could house a family of four. A city can meet its production targets on paper while its actual capacity to house residents declines. Santa Monica has been mandated to add 8,874 units under state housing requirements, and city staff has proposed capacity for 52 percent more than that figure. Yet the community is shrinking. Our schools now import 17 percent of their students from outside the district because local units no longer translate into local children.

The economics driving this transformation are brutally straightforward. Developers favor studios and one-bedroom units because they generate 36 percent more profit per square foot than family-sized apartments. This calculus has resulted in one-bedroom units dominating 51 percent of all new national construction. As UCLA urban planning professor Michael Storper argues, “The supply you get is the wrong kind of supply.”

The YIMBY belief is that more housing lowers prices by ‘filtering’, wherein new luxury construction frees up older units for lower-income residents. This concept flounders on a basic reality: housing is not interchangeable. A studio optimized for a transient professional does not become a family home when it ages. As one economist notes, when people get richer, they do not demand more housing units; they demand nicer housing, which increases prices without increasing the functional supply.

In expensive urban markets, solo dwellers often possess above-average incomes, allowing them to outbid families for limited inventory. In Santa Monica, the consequences create attacks on families from both at the entry level, where solo dwellers can claim smaller units that should serve as stepping stones for young households, and at the upper end, these same affluent persons also claim two-bedroom units, leaving bedrooms empty while families are priced out to distant suburbs like Riverside. Meanwhile, the median one-bedroom rent is $2,350, yet the units themselves continue shrinking, becoming smaller year over year. Recent research modeling supply-side solutions found that even increased construction rates would require 18 years to make a median one-bedroom affordable for a worker without a college degree —or inordinately longer if price declines are modest. This is no way to address affordability.

Solo dwellers represent the most housing-inefficient household type from a resource utilization perspective. As the percentage of solo households increases faster than overall population growth, it amplifies housing demand beyond what population numbers suggest. Economic pressures that delay marriage and childbearing extend the period of single-person household formation, prolonging demand for individual units. And solo dwellers disproportionately prefer urban locations with amenities and employment, concentrating demand in markets that are already impossibly tight.

Traditional housing metrics have become increasingly misleading. Santa Monica maintains a 10 percent residential vacancy rate, yet rents continue climbing because the housing stock has been optimized for the demographic least efficient at using it. State-level interventions often exacerbate rather than ameliorate the problem. Accessory Dwelling Unit legislation, while intended to increase density, frequently targets affluent solo renters rather than providing affordable family options. Builder’s Remedy projects in Santa Monica average 90 percent market-rate units, which are almost exclusively transient studios designed for maximum developer return rather than community stability.

Overall, the language of housing policy has been colonized by the ‘gentrified mindset’—a framework that treats market-rate development as an engine while equity is a mere mitigation measure. We argue about “equitable development,” “inclusive growth,” and “affordable housing percentages,” all driven by the premise that displacement is the baseline and protection is the exception. “Housing production” sounds administrative and positive; “demolishing rent-controlled units to build luxury studios” reveals the same activity in concrete terms. Improvement becomes displacement precisely when improvements are not for our current residents. The result is curated diversity—a difference that is aesthetic rather than substantive, an Epcot Center’s model of urbanism.

Addressing this challenge requires moving beyond raw unit counts toward utilization efficiency. Occupancy standards that link unit size to household size would ensure square footage serves the maximum number of inhabitants. The 1.2 million square feet of vacant office space in Santa Monica presents an opportunity for adaptive reuse into family-centric housing rather than additional studio towers. Three-bedroom (less than 5% of new construction since three one-bedroom units generate 36% more profit) — mandating these would ensure the city supports intergenerational residents.

Community Land Trusts offer an alternative ownership model that operates outside gentrification’s logic entirely, using 99-year ground leases to ensure permanent affordability and immunity from market volatility. Unlike developer-driven projects focused on profit-maximized studios, CLTs prioritize community-owned assets and can acquire and rehabilitate existing family-sized apartments. Vienna’s social housing model offers another template—housing de-commodified as a public utility rather than an investment vehicle. These approaches require confronting property as an institution, not just regulating its excesses.

The solo dwellers are not inherently problematic—they reflect changing social patterns and individual preferences that deserve accommodation. Recognizing this does require thoughtful adaptation of housing stock and policy to ensure adequate supply for all household types. The current approach, which treats unit counts as the primary metric of success while ignoring who actually lives in those units, has produced a city that meets its housing targets while hemorrhaging families.

Until housing policy confronts the mathematics of efficiency, Santa Monica will continue replacing a rooted community with an investment vehicle that is functionally uninhabitable for families. The physical city expands while the functional city contracts. We are building housing that does not house, adding capacity that does not add capacity. The choice before us is whether to continue optimizing for the profitable forgetting of community or to implement strategies that treat the city as a home rather than merely real estate. The mathematics are unforgiving, but they are not immutable. These changes are, in the end, a policy choice that can be modified with our votes.

Jack Hillbrand, Architect, for SMa.r.t., Santa Monica Architects for a Responsible Tomorrow.

Mario Fonda-Bonardi AIA, Former Planning Commissioner, Robert H. Taylor AIA, Dan Jansenson, Former Building & Fire-Life Safety Commissioner, Sam Tolkin, Former Planning Commissioner, Michael Jolly ARE-CRE, Jack Hillbrand AIA, Landmarks Commission Architect, Phil Brock (Mayor, ret.), Matt Hoefler, NCARB, Architect, Heather Thomason, Community Organizer.